Each exercise bout should be preceded by an 8- to 10-minute warm-up and followed by a cool-down period of equal time. Both are integral components of an exercise program. Proper warm-up and cool-down contribute to performance and the exerciser’s health and safety. Sandwiched between these two components is the actual exercise program – in this article, walking and jogging.

The warm-up is designed to prepare the body gradually for more vigorous exercise. In approximately 10 minutes of warming up, the muscles to be involved in the activity are heated and the heart rate is allowed to increase slowly toward the rate expected during the actual workout. Rhythmic calisthenics, walking, slow jogging, and other low-intensity activities can be used during the warm-up to prepare the individual for exercise of greater intensity. These activities smooth the transition from inactivity to activity with minimum oxygen deprivation to the heart, muscles, and organs.

Without a proper warm-up, the heart rate would rise rapidly, forcing the body to rely upon short-term supplies of fuel to generate the energy needed for exercise. Circulation does not increase in proportion to heart rate; during a brief interval (about 2 minutes) the heart and other muscles are not fully supplied with oxygen. Early studies showed that sudden strenuous exertion without the benefit of a warm-up period produced abnormal cardiac responses that reflected oxygen deprivation, ventricular arrhythmias, and left ventricular dysfunction. Later studies of healthy subjects have not confirmed the same cardiovascular abnormalities as previous studies. In fact, even stable post-myocardial patients (heart attack patients) who had been treated with beta blocker medication did not respond abnormally to sudden exertion.

At the worst, the potential for inducing a cardiovascular event during sudden physical exertion may be higher without warming up. At the least, it produces significant discomfort during the first 2 to 3 minutes after beginning exercise, and it increases the likelihood of incurring a musculoskeletal injury. This is a potentially dangerous time, particularly for those whose circulation is compromised by heart and blood vessel disease.

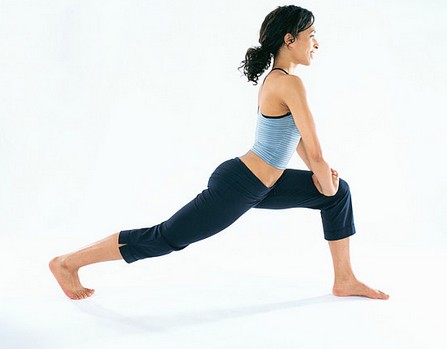

When the cardiorespiratory warm-up phase is complete, the muscles are stretched. At this point the walker or jogger should be sweating—indicating that the core temperature might be elevated slightly and muscle temperature is substantially elevated. Both responses enhance performance and reduce the risk of physical injury. Muscles are stretched more effectively when they are heated.

The preferred method for enhancing and maintaining flexibility of the joints and elasticity of muscles and connective tissue is static stretching. This consists of slow, controlled movements and desired end positions that are held for 10 to 30 seconds. The desired end position should produce a feeling of mild discomfort but not pain. If the stretch is painful, you are stretching too forcefully and are in danger of exceeding the elastic properties of muscles. Static stretching is effective because:

- It is not likely to cause injury.

- It produces no muscle soreness.

- It helps to alleviate muscle soreness.

- It requires little energy.

Static stretches are effective and convenient, they do not require the assistance of a partner, and no equipment is necessary.

Another technique for increasing flexibility is proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF). Physical therapists have used PNF stretching for many years with patients who have neuromuscular disorders. It is more effective than static stretching in improving flexibility, but it does have limitations.

1. Most PNF techniques require the assistance of a partner who is competent in this system, so as not to injure the exerciser.

2. Using PNF techniques takes more time.

3. PNF is associated with more pain and muscle stiffness.

4. PNF techniques are more complex and more difficult to learn than static stretching procedures.

For these reasons, even though PNF stretching is slightly more effective than static stretching, it is not the preferred method.

Dynamic or ballistic stretching is not recommended because it forces muscles to pull against themselves. This type of stretching entails bouncing and bobbing movements that activate the myotatic reflex. Each rapid stretch sends a volley of signals from the stretch reflex to the central nervous system, which responds by ordering the stretching muscles to contract instead.

If you have dozed off while sitting in a chair, you probably have experienced the results of the stretch reflex responding to rapid stretch. Your head drops forward as you nod off, causing the neck muscles to stretch rapidly. This sudden dynamic stretch sets in motion the reflexive process that results in rapid contraction of the neck muscles and a quick return of the head to the upright position. The rapid movements in opposite directions can result in muscle soreness and possible injury.