Recently, my grandmother moved out of her home of more than 50 years. She loved her home and didn’t want to leave, and she was fully capable of living there alone, as she had for many years already. But there was only a tiny half-bath on the first floor, no room for a larger one, and a forbiddingly steep staircase separating her from the full bath on the second floor. Active, healthy, and still a lot sharper than I’ll ever be, she just was unable to coax her 90-year-old legs up those stairs any more.

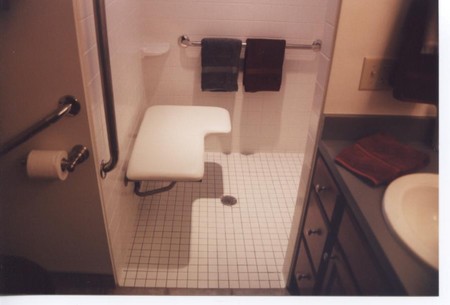

Accessibility is a real issue. In my grandmother’s case, simply having room for a full bath instead of a half-bath on the first floor would have allowed her to remain in her house. In other cases, bathrooms need to be adaptable to people with walkers, or people who use wheelchairs, or people with other physical limitations. Because bathrooms serve such a specialized and necessary function, they should be planned for a lifetime of use by people with a wide range of abilities. It is simply unrealistic to expect that a household will never need a bathroom facility to accommodate people who get old or who have physical limitations. This doesn’t necessarily mean that specialized—and therefore expensive—equipment is required. Space planning can go a long way toward making a bathroom accessible. So can the judicious use of grab bars and handholds. In some instances, specialized fixtures might become necessary, but usually adapting conventional fixtures by providing plenty of room, sufficient handholds, and supplemental access is enough.

In many cases, neglecting the issue of accessibility is prohibited by law. Federally funded housing projects and commercial construction typically fall within the jurisdiction of standards published in such guidelines as the American National Standards Institute’s All7.1 (updated in 1981 to include standards for private dwellings), the Uniform Federal Accessibility Standard (UFAS) of 1985 (for dwellings in federal projects), the 1988 Fair Housing Amendments Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. While these laws don’t all have the same specific provisions and don’t generally apply to private residential construction, their common goal—to provide equal access to bath facilities for people with a wide range of abilities—can and should be incorporated into residential design.

Sometimes, simply making the bathroom adaptable—that is, capable of being altered by adding or removing certain elements—for persons with varying degrees of disabilities is enough. This can mean providing blocking in the framing to accommodate the installation of grab bars or installing a base cabinet under a sink that can be removed later to provide knee space for someone in a wheelchair.

Sometimes, though, accessibility considerations challenge conventional construction wisdom and economics. The fact that first-floor half-baths can be inserted into such small spaces at relatively small expense is one of the reasons why they are so popular. A full-size bath undoubtedly requires more floor space. But an accessible or adaptable bathroom need not be prohibitively large and can fit in a relatively compact 5-ft. by 7’/2-ft. space.

If at all possible, each level of living space in a house should have at least one full-size bath or the capability to accommodate a full-size bath with minimal renovation. One economical approach is to frame and rough-plumb the bath to accommodate a full-size tub but hold off on installing the fixture itself. This 3-ft. by 5-ft. area can be converted to closet space with access either from inside or outside the bathroom. If doorway locations and framing headers are planned in advance, it’s relatively easy to patch in or remove screwed-in studs and drywall when the time comes to remove the closet and install a tub, and few people will argue against the extra—though temporary—storage space.