Three-year-old Cody Smith knew what the word sharing meant; it meant that he couldn’t sit and hold as many toys as he wanted when his friend, Jim, came over to play. “You must share!” Cody’s mother told her son after another day of Cody clutching his toys and saying “Mine” whenever his mother said, “Now, Cody, let’s share”

One day Mrs. Smith screamed, “I’m going to give all your toys to poor children who will appreciate them” as she spanked Cody into tearfully giving up his toys. That night after Cody was tucked in bed, Mrs. Smith told her husband, “Cody just doesn’t know how to share.” This simple statement ished new light on the problem. The Smiths realized that they needed to teach Cody what sharing meant.

The next time Cody’s cousins came over, Mrs. Smith took him aside fora talk. “Cody, here’s the new sharing rule. Anyone can play with anything in this house as long as another person is not holding it. If you or Mike or Mary is holding a toy, no one can take it away. Each of you may play with only one toy at a time” Mrs. Smith also told Cody that he could put away one favorite toy, which could belong to him and him alone.

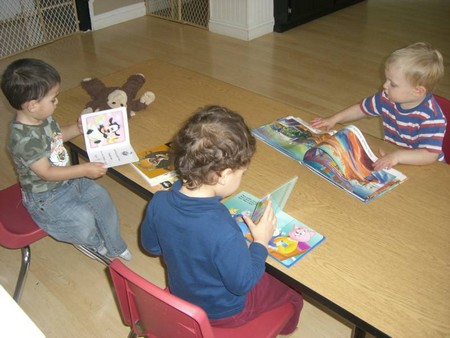

The next few hours were tense for Mrs. Smith, but Cody seemed to be more relaxed. He began by holding only one toy and letting his cousins have their pick of the lot in the toy box. “I’m so proud of you for sharing,” his watchful mother praised him as she oversaw the operation.

When she ventured off to fix lunch, the familiar “Mine” cry brought her back to the playroom. The new <€burp-itself” doll was being pulled limb from limb by Mary and Cody. “This toy is causing trouble,” Mrs. Smith stated matter-of-factly. “It must go to Time Out.” The children stared in disbelief as they watched poor Betsy sitting in the Time Out chair looking as lonely as a misbehaved pooch. After two minutes, Mrs. Smith returned the toy to the children, who had long since forgotten about it and were busy playing with blocks.

As the weeks went by, the children played side by side with fewer Time Outs needed to restore peace, particularly since Cody was more open to letting “his” toys be “their” toys during the play period.

Not Wanting to Eat

Parents often find themselves pushing their on-the-go preschoolers to eat, since many children under six are too busy investigating their world to take much time out for food. If the temptation to force food on your child seems overwhelming, try giving her more attention for eating (even the smallest pea!) than for not eating.

Note: Preschoolers are notorious for their occasional bouts of not wanting to eat; don’t mistake these for illness. However, get professional help if you feel your child is physically ill and can’t eat.

Preventing the Problem

Don’t skip meals yourself.

Skipping meals yourself gives your child the idea that not eating is okay for her, since it’s okay for you.

Don’t emphasize a big tummy or idolize a bone-thin physique.

Even a three-year-old can become irrationally weight conscious if you show her how to be obsessed with her body.

Learn the appropriate amount of food for your child’s age and weight.

Growth rate, activity level, and physical size determine how many servings from the five food groups (milk, meat, vegetable, grain, and fruit) a child needs each day. Consult your child’s health-care provider for answers to specific nutrition questions about your child. For more information about recommended guidelines for one- to five-year-olds, consult the National Dairy Council’s website at www.nutritionexplorations.org.

Solving the Problem

What to Do

Encourage less food, more often.

Get your child’s system in the habit of eating meals at particular times during the day. However, your child’s stomach isn’t as large as yours, so it can’t hold enough food to last four or more hours between meals. Let your child eat as often as she likes, but only the right foods for good nutrition. For example, say, “Whenever you re hungry, let me know, and you can have celery with peanut butter or an apple with cheese.” Make sure you can follow through with your suggestions, based on what foods are available and what time a bigger meal is coming.

Let your child choose foods.

Occasionally let your child choose her between-meal snack or lunch food (with your supervision). If she feels she has some control over what she’s eating, she may be more excited about food. Offer her only two choices at a time, so she doesn’t become overwhelmed with the decision-making process, and praise her choice with comments like, “I’m glad you chose that orange. It’s really a delicious snack.”

Provide variety and balance.

Children need to learn about proper diet, which involves a wide range of foods. Expose your child to the various tastes, textures, colors, and aromas of nutritious foods. Remember that preschoolers’ tastes often change overnight, so expect your child to turn down a food today that was a favorite last week.

Let nature take its course.

A normal, healthy child will naturally select a balanced diet over a week’s time, which pediatricians say will keep her adequately nourished. Keep a mental note of what your child has eaten from Monday through Sunday¡ªnot from sunup to sundown, before becoming alarmed that she’s undernourished.

Catch your child with a mouthful.

Give your child encouragement when she downs a spoonful of nutritious food, to teach her that eating will bring her as much attention as not eating. Praise good eating habits by saying, “That’s great the way you put that meat loaf in your mouth all by yourself,” or, “I’m glad you like the rolls we have today.”

Establish regular mealtimes.

Because your child is not on the same eating schedule as you, she may often want to play outside or finish block building when your mealtime arrives. She may need to be trained to switch to your schedule for sitting together. Do this not by forcing your child to eat a lot of food, but by setting a timer for the length of time she must remain at the table, eating or not. Say, “The timer will tell us when dinner is over. The rule is that you must stay at the table until the timer rings. Tell me when you’re done eating, and I’ll remove your plate.” Let children under three stay at the table a shorter time (not more than five minutes) than four- or five-year-olds (not more than ten minutes). Identify the times when your child seems to get hungry, to learn what kind of hunger clock she’s on (which you could switch to, if possible).

What Not to Do

Don’t offer food rewards for eating.

Keep food in its proper perspective. Food is meant to provide nourishment, not to symbolize praise. Instead of offering your child ice cream for eating her vegetables, say, “Since you ate your green beans so nicely, you can go outside after dinner.”

Don’t bribe or beg.

When your child is not eating, don’t bribe or beg her to clean her plate. This makes noneating a game to get your attention, which gives your child a feeling of power over you.

Don’t get upset when your child won’t eat.

Giving her attention for not eating makes not eating much more interesting to your child than eating.

Don’t overreact.

Downplay the attention you give to your child’s not wanting to eat so eating time does not become a battleground on which you wage power struggles.