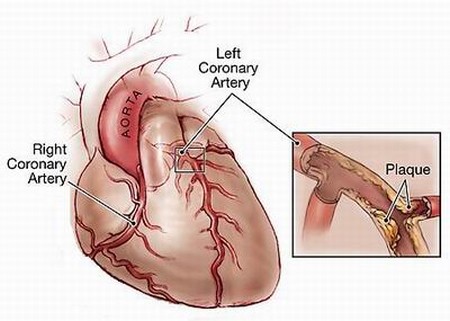

Atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries, results from an accumulation of calcified fatty plaque in the blood vessels. Atherosclerosis has been called a “silent killer.” For one out of four victims, the first sign of trouble is sudden death. Lesions in which function has been impaired by atherosclerotic growths develop in Western man at an average age of 20. These lesions spread so that they cover about 2 percent more of the surface of the coronary arteries every year. By the time 60 percent of this surface has been covered with coronary lesions, the opening through which blood passes is narrowed enough to set the stage for trouble. Until they reach this critical threshold, however, these lesions cause no symptoms. Then they can take only minutes to manifest as a fatal heart attack. Besides heart attacks, atherosclerosis is the chief cause of coronary heart disease (CHD) and strokes it is a major cause of high blood pressure and contributes to circulatory disorders, including Raynaud’s disease.

Heart disease was rare at the turn of the century, accounting for only 8 percent of U.S. deaths. Today, it has shot up to the number-one killer, accounting for 45 percent of all deaths. Dietary cholesterol is commonly blamed for the epidemic, based on the Framingham Heart Study, in which 5,209 adults living in Framingham, Massachusetts, were followed for 18 years beginning in 1949. People with lower blood pressure and serum cholesterol levels were found to live significantly longer than people with higher levels. Long-term studies of people on low-fat, high-fiber vegetarian diets have also consistently shown a reduction in serum-cholesterol and blood-pressure levels, as well as an actual increase in fife expectancy.

One snag in the cholesterol theory is that since 1990, dietary cholesterol has steadily gone down, not up. The consumption of other suspect foods, however, has increased. Foods on the increase that have been linked to increased heart disease risk include vegetable (not animal) fats, sugar, and heated milk protein. The latter has been shown to increase the formation of blood clots, or thrombosis.

Problems with the cholesterol theory have prompted some researchers to revive the theory that heart disease results, not from dietary cholesterol, but from the toxins from which it is protecting the arteries. The body itself produces cholesterol, which accumulates in the form of plaque in the arteries as a protective mechanism. Cholesterol is necessary to repair injuries and protect against irritation to the arterial wall. Cholesterol is also the stuff of which hormones are made. Without enough of it, your body will be hormone-deficient. Dietary cholesterol can be dangerous, but research has shown that the dangerous form is the cholesterol that has been oxidized by high temperatures and exposure to air. Antioxidants can help protect against this form of damage.

The Conventional Approach

The conventional approach to preventing heart disease is to use drugs to reduce its major risk factors: high blood pressure and high cholesterol levels. The problem is that the long-lived people in the studies pinpointing these targets didn’t get their low blood pressure and cholesterol levels from drugs. They got them from their lifestyles or their genes. In most studies in which these risk factors have been lowered with drugs, long-term benefits have been disappointing. Recent studies have actually linked the drugs used as mainstays to lower blood pressure—beta blockers and calcium channel blockers—to an increased risk of death from heart disease. For a detailed discussion of studies of their long-term effects, see “Hypertension,” “Cholesterol, High.”

Pharmaceutical estrogen is another drug that has been promoted as lowering heart disease risk. On January 18, 1995, JAMA reported the results of the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial, the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective study of the effects of estrogen on cholesterol and triglyceride levels. It found that estrogen significantly increased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, the “good” cholesterol). HDL-C is thought to be the best predictor of heart disease risk in women: the higher the HDL-C, the lower the risk.

Confounding the issue was the fact that triglycerides also went up in women on estrogen, suggesting an increase in heart-disease risk. And taking synthetic progestins with the estrogen (the hormone-replacement protocol popular in the United States) reduced the HDL-C benefit by a full 75 percent. Meanwhile, a second PEPI report, issued in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) on February 7, 1996, strongly advised women who still had their uteruses not to take estrogen alone, due to a substantially increased risk of endometrial cancer.

Still to be proven is that the effects of estrogen on HDL-C translate into an actual increase in survival. In 1997, researchers reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine that neither the current nor the long-term use of estrogen, either alone or with synthetic progesterone, significantly affects the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) in postmenopausal women. Offsetting the lack of a heart-protective effect for estrogen is an increased risk of breast cancer, another growing epidemic. Researchers writing in the British medical journal Lancet in 1997 reported that breast cancer risk is increased after only one year of estrogen use, and that it increases thereafter by almost 2.3 percent per year. These findings were based on a review of about 90 percent of the worldwide epidemiological evidence, including 51 different studies.

In short, the drug approach merely delays death from heart disease; and whether it does even that has yet to be unequivocally established.